More than two-thirds of the population of the tropics — about 2.7 billion people — directly depend on nature for at least one of their most basic needs, according to new research.

The study, published today in the journal Global Environmental Change, is the first to quantify people’s dependence on nature, and underscores the extent of the threat that climate change and the destruction of nature pose to human life.

Conservation News spoke to the study’s lead author, Conservation International scientist Giacomo Fedele, about the many ways humans are nurtured by nature, the biggest threats tropical ecosystems face and how countries can promote climate justice for the world’s most “nature-dependent” people.

Question: Who is considered “nature-dependent,” and where are these communities located?

Answer: We define nature-dependent people as those who use natural resources to meet at least one of the four basic human needs: drinking water, housing materials, energy for cooking, or livelihoods. Taking it one step further, we found that 1.2 billion people are “highly nature-dependent,” meaning that they rely on natural resources for at least three out of four of those needs.

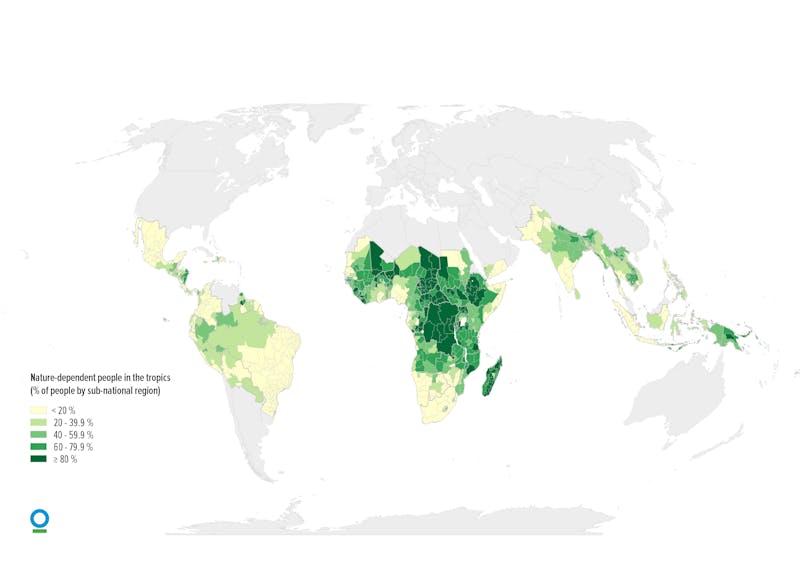

After analyzing interviews with more than 5 million households in 85 tropical countries, we found that the greatest proportion of highly nature-dependent people in the world is located in the tropics of Africa, making up nearly half of the population — 478 million people — in that region. Concentrated in the Congo Basin and East Africa, most of these people rely on nature for all four of their basic needs, but have a particular reliance on wood and charcoal as fuel for cooking.

On the other side of the globe in the Asia-Pacific region, 278 million people —more than a quarter of the population — can be considered highly nature-dependent, with the highest proportion in New Guinea, the lower Mekong basin and the Ganges River basin. In these areas, ecosystems are critical for providing energy and housing materials.

In tropical countries throughout the Americas, 9 percent of the population — 48 million people — depend deeply on nature for their livelihoods, practicing agriculture, harvesting forest products or fishing. The majority of nature-dependent people in this region live in the upper Amazon plains, Guyana and Central America.

Q: What makes your research unique?

A: It is well-established that ecosystems — and their ability to store carbon — play a huge part in helping to fight climate change. In fact, research shows that they can provide 30 percent of the emissions reductions necessary to stabilize the climate.

However, what we’ve been missing is quantitative data on where the most important places are to protect nature for the climate and for people.

This information — which our map can now help provide — is crucial because climate change poses a huge threat for nature-dependent people in the tropics. At its core, this is a climate justice issue: Nature-dependent communities often contribute the least to global greenhouse gas emissions, yet they often feel the most severe impacts of the climate crisis — from rising sea levels to severe heat waves.

Q: How can this map help inform policies to address this climate justice issue?

A: Knowing where nature-dependent people live can help governments and decision-makers implement effective conservation and sustainable development strategies based on what resources these communities rely on the most. And it’s not just climate change we have to worry about: Even small changes to the environment can have an enormous impact nature-dependent people. Depending on where you are in the tropics, threats include logging, unsustainable farming practices and mining — all of which can reduce access to food and clean water, building materials and endanger livelihoods.

This is why policies and conservation interventions are going to vary from place to place — and why it is crucial to take into consideration the needs and aspirations of local people when designing and implementing conservation strategies.

For example, creating protected areas that limits human activity may be appropriate in some areas in countries like Suriname or Guyana, which have intact ecosystems and fewer nature-dependent people. But that same strategy may be less effective in areas with a high number of nature-dependent people, in countries such as Cambodia or the Democratic Republic of Congo. There, communities could benefit more from implementing sustainable techniques to manage their land, like community-based natural resource management or climate-smart farming.

Our study outlines how nature-based strategies that protect, restore or sustainably manage ecosystems can be carefully designed to promote inclusive human development and environmental benefits.

Q: Conservation International is implementing a project in southern Africa that addresses some of these issues. Can you tell us a bit about that?

A: Local and Indigenous communities such as the Mnisi peoples near Kruger National Park in South Africa and communities in the Limpopo National Park of Mozambique have raised cattle for generations, but unsustainable practices such as overgrazing have degraded their grassland ecosystems over time.

Conservation International’s Herding 4 Health program is helping farmers across six African countries — and more than 1.5 million hectares (3.7 million acres) of rangeland — implement wildlife-friendly and climate-smart farming techniques to restore the nature that they depend on. Through the program, rural communities are supported by trained herders to voluntarily implement planned grazing of their livestock to minimize overgrazing, remove invasive vegetation that hamper grass growth and water availability, and adopt human-wildlife conflict mitigation practices. In return, they receive support to improve the quality and health of their livestock, reduce animal losses from wildlife predators and access to livestock markets.

One of the most critical components of this project is that it takes into account the priorities and needs of the nature-dependent farmers, who stand to lose the most if grasslands continue to deteriorate. Putting nature at the heart of sustainable development is the best way to benefit the climate, wildlife and people.

Kiley Price is the staff writer and news editor at Conservation International. Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Donate to Conservation International.

Cover image: Children play in a tributary of the Volta River near Nabogu, Ghana (© Benjamin Drummond)

Further reading: