Above: A sea turtle swimming in the Pacific Ocean.

Sea turtles don’t care about maritime boundaries.

Yet national borders affect them just the same. Sea turtles’ nesting grounds and feeding grounds are typically in different parts of the ocean, in different countries — and subject to different protections.

Knowing where the turtles go is the first step to protecting them. To that end, Conservation International and partners placed satellite tags on 10 of them, to track them in real time as they meandered around the Coral Triangle, an area of waters in Southeast Asia and the western Pacific Ocean that are home to the highest concentrations of marine life on Earth. (You can follow the turtles’ paths online by clicking here.

Recently, Human Nature sat down with Niquole Esters, director of Conservation International’s Coral Triangle Initiative, to talk about how one tags a sea turtle, where exactly these turtles seem to be going, and what a changing climate means for these charismatic and endangered species.

Watch the video from the tagging project here.

Question: Why did you choose to tag turtles?

Answer: The short answer is everybody loves turtles. Kids to adults to young people to women — who doesn’t like a turtle?

Another thing is that each of these turtles functions in a different environment, which can then tell us something about that environment. Green turtles feed on seaweed. Hawksbill turtles mainly eat sponges from coral reefs. So, if you’re looking at protecting those turtles, you need to protect the ecosystems they live in.

Q: How do the tags work?

A: We attached satellite tags to the carapace, which is the shell of the turtle, and they send us data, in real time, about the turtles’ locations as long as we want them to. In this case, we tagged them in December and we stopped getting data at the end of March.

Q: How did you tag the turtles?

A: We patrolled the beaches about every four hours looking for tracks. We followed the tracks to find a turtle and waited for the opportune time to tag it. When the turtle is nesting, it goes into a zone — it’s so focused on what it’s doing that it doesn’t notice the things around it. If we were lucky, we could find the nest and tag the turtle while it was nesting because it wouldn’t notice us.

Turtles are quite canny. They camouflage themselves. So sometimes we missed the turtle or couldn’t find it. Sometimes the turtle would climb up on the beach, decide that it doesn’t like it and move on to another nest. Then it would start that one and decide that it doesn’t like that one either. They can do that three or four times and then they’ll nest. We would try to find it at night without being too loud since it might be scared away.

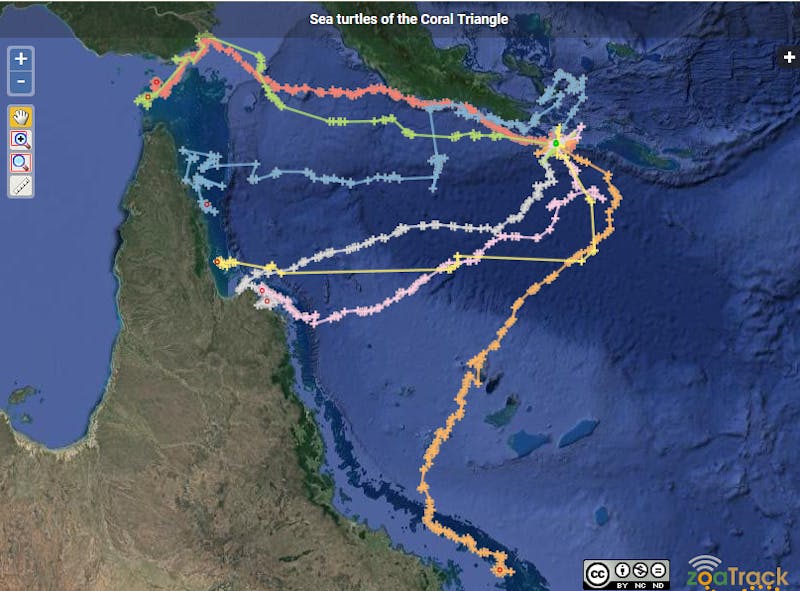

The paths of seven different sea turtles in the Coral Triangle.

Q: What did you find that surprised you?

A: We were surprised to find hawksbill turtles. They are critically endangered. The sea turtle expert who was with us lit up when we found the hawksbill tracks, as we were only expecting green turtles.

We also found that the turtles are migrating to Australia. This information starts to open up avenues for conservation and for partnership across countries. The whole sea turtle pathway includes the Great Barrier Reef and the Coral Sea, which is bigger than a marine protected area on a tiny island. These guys move and swim hundreds and thousands of miles. We have to protect them in their entire life cycle because they nest and feed in different areas.

The turtles that we tagged went from Timor-Leste to Australia and from Papua New Guinea to Australia. That means we should really be thinking about how we can partner with Australia. How can we partner with marine protected areas in those places so that the whole journey of the turtle is protected?

Q: How does climate change play into the turtles’ survival?

A: During the expedition, we went to a lot of little islands and noticed almost immediately by the stories we were hearing that the islands were all shrinking. If these islands are supposed to be nesting sites for these turtles, what happens when the islands disappear? One of the staff from our partner Eco-Custodian Advocates, who was also on the expedition, said, this island is going to be gone in 10 years. This is a real thing.

The islands are shrinking so much but the turtles are still coming, so they’re digging up each other’s nests because their imperative to nest is so overwhelming. In fact, the sea turtle expert told us of seeing when a turtle doesn’t make it to the beach in time: They end up laying their eggs in the water on the way to the beach. If they get to the beach and they have to nest, they’ll make a hole and they’ll drop their eggs — sometimes they’ll end up digging up other eggs. If the islands are shrinking, then there’s less real estate for everyone.

Q: How did the communities respond to your work?

A: Each of these island communities has distinct customs and diets. Some of them eat giant clams. One particular community in Papua New Guinea is known for eating sea turtles. So our approach was not to tell them that they can’t eat a sea turtle, because we do not have that right; they need to feed their families. However, we talked with them about avoiding eating 50 sea turtles at once and consider other options. We said to eat only the ones that they really need and then mix it up with some fruits, vegetables and other seafood.

Many community members have now started advocating for turtles in their own communities. They’ve said that they want to apply for government funding for turtle protection. That’s what we really want — something that galvanizes people to take action and make their own decisions. At the end of the day, you want them to do it on their own.

Q: What’s next for the sea turtles?

A: We want to tag more turtles across several years and several seasons. Ideally you want to tag over the course of a few years to get the full picture of where the turtles are going and where they’re coming from.

Morgan Lynch is a staff writer for Conservation International.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Donate to Conservation International.