This post was updated on May 31, 2022.

In the most comprehensive review yet of the risks facing reptiles, scientists find that more than a fifth of all these species are threatened with extinction.

A new study, published today in Nature, assesses more than 10,000 reptiles around the world — from turtles, snakes and lizards to crocodiles — and warns that humanity must conserve them to prevent dramatic changes to Earth’s critical ecosystems.

“Reptiles are one of the most diverse groups of vertebrates — we’re talking about species that have been largely overlooked in conservation studies — and the potential loss is striking,” said Conservation International scientist Neil Cox, who co-led the study.

“This threat analysis is the most extensive to date. We’ve found more reptile species are threatened than birds, a sign that global efforts to conserve them must be ramped up.”

A photograph of a Carter's Semaphore Gecko (Pristurus carteri). The species is endemic to Oman. (© Johannes Els)

The edge of extinction

In evolutionary terms, reptiles have had a very successful track record — surviving catastrophic meteors, continental drifts and fluctuating temperatures over hundreds of millions of years.

But in the Anthropocene, an era dominated by human impacts, their resilience may be coming to an end, according to Cox.

“Our data shows that reptiles are increasingly threatened by widespread habitat loss driven by logging and agricultural expansion” he said. “Increased reptile extinctions could throw food chains around the world off balance because these species play an indispensable role in ecosystems as both prey and predators for many other species.”

A photograph of an Armadillo Girdled Lizard (Ouroborus cataphractus) taken in South Africa. The lizard is in its defensive posture (© Johannes Els)

Combining extinction risk data from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and input from more than 900 scientists around the globe, the study’s authors found that threatened reptiles are concentrated in tropical areas such as Southeast Asia, West Africa and northern Madagascar — where deforestation rates are particularly high.

And another threat looms on the horizon for these scaly species: climate change.

“As ectotherms — species that depend on external sources of body heat — reptiles are particularly vulnerable to changing temperatures fueled by climate change,” said Cox, who is the manager of the joint IUCN-Conservation International Biodiversity Assessment Unit. “In dry, arid areas such as the desert, many reptiles are already living at the edge of their heat tolerance. A small increase in temperature could make their habitats unlivable.”

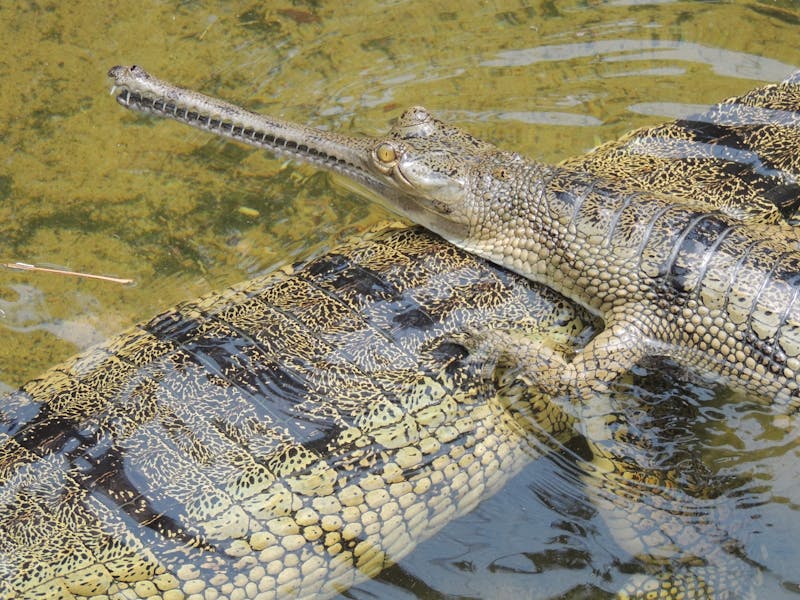

A photograph of a Gharial or Fish-eating Crocodile (Gavialis gangeticus), which is a critically endangered species. The photograph was taken in India (© Johannes Els)

Targeting conservation efforts

While the findings of this study are bleak, there is a silver lining, said Cox.

“Determining what activities are harming reptiles also gives us insight into how we can protect them,” he said.

For example, in India, urban development is pushing a species known as Thackeray's dwarf gecko to the brink of extinction. Armed with this information, local conservationists can develop strategies to protect the gecko, such as creating a conservation management area to prevent habitat loss.

The study found that many global conservation initiatives implemented for other species will likely benefit reptiles, particularly in the tropics. However, more targeted efforts will be necessary to protect the most vulnerable reptile species, such as heavily exploited freshwater turtle species, said Cox.

A photograph of an Arabian Helmeted Turtle (Pelomedusa barbata). The endangered species is endemic to Arabia, including southwestern Saudi Arabia and Yemen. (© Johannes Els)

As world leaders prepare to meet later this year at the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity in Kunming, China, the study’s reptile data can help inform negotiations to protect Earth’s biodiversity over the next decade.

“Now that we have a global assessment of what’s hurting reptiles, we can incorporate this data into our conservation practices and policies,” he said. “It’s time to give reptiles their due. We cannot let this group of animals, which have survived on Earth for millennia, fall through the cracks of conservation efforts.”